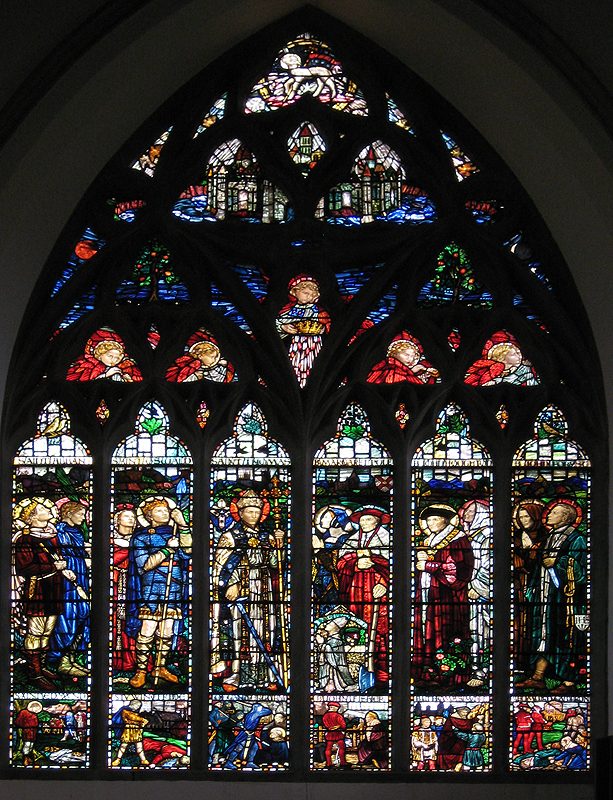

In the bottom left hand corner of Marga’s Great West Window at Shrewsbury (pic right) is a small scene that has drawn some attention lately: her puzzling depiction of the Anglo-Saxon legend of the martyrdom of Saint Winefride. In this realisation of the story, it is the vicious attacker who is the centre of attention, while the slain young woman is a secondary, prone figure, and the restorative miracle to come is almost completely ignored.

Why depict the legend in this defeatist way?

Winefride

St Winefride is a significant figure in the Welsh-English borderlands, an area which has Shrewsbury at its heart.

The site of her beheading is still commemorated at the shrine of Holywell in North Wales and, when her relics were brought to Shrewsbury in the Middle Ages, she was adopted as the town’s local patron saint; and Shrewsbury Abbey became another centre of her cult. (Even today, in Shrewsbury Cathedral, a whole chapel is devoted to her and her story).

Shrewsbury-born Marga surely picked up on this devotion, and eventually depicted Winefride no less than three times – particularly in the Winefride window at Newport.

The villain of the piece

There are a number of curious things about Marga’s depiction:-

What do the eyes on the killer’s tunic represent?

Why is the killer the centre of attention? And why is the happy end to this story not alluded to?

Why is the scene so … stagey?

The killer is a prince called Caradoc, who confronts Winefride as she leaves chapel, but then, furious at being rebuffed in his desires by her, cuts her head off. Thus, the eyes on his tunic, according to scholar Roger Hall, symbolise his overweening sexual chauvinism – being, says Roger, ‘the lust of the eyes’ (ref: 1 John 2:16).

As for Winefride, the pathos of her plight is emphasised by the fact that her head is rolling out of the panel’s frame, as is her poor hand – though, in what’s been described as a ‘touching kindness’, the artist has covered the dead face with a headscarf. But – very strangely -, there is no allusion to the rest of the legend, in which, almost immediately, the saint will be miraculously restored to life and her attacker punished. In Marga’s depiction, Caradoc appears to have won…

Is Margaret, just twenty-eight years old at this time, perhaps making an autobiographical point? There is a family anecdote that Margaret had been badly bruised by love early in life and had retreated into herself. Indeed (though we don’t really know) she seems not to have gone in for sexual love during her life.

Although so much work has gone into this scene and the fact that it is full of marvellous colouring (especially that louring sky), this panel is just a very small part of the huge West Window. Actually, it’s quite high up and its details hard to see with the naked eye – and Marga would have known that this would have been so. Was she saying something personal, but not wishing to be overt?

Commentators have also raised a third question: why is Caradoc such a stock stage villain? With his double eye-brows and emphasised stance, he reminded one commentator of “… the Victorian actor Gustaf Gruendgens playing Mephistopheles, who in turn took the Gustave Dore illustrations of the Faust story as inspiration.”

It’s tempting to think that Marga attended the Shrewsbury Music Hall popular theatre, one of the many Edwardian ‘blood tubs’, (so-called because of the heavy diet of melodramas they put on). A blustering but evil character, similar to this Caradoc, would have been seen there week after week.

By turning the killer into a stage-villain, is Margaret trying to reduce him down to an arrogant and shallow bully? Maybe.

An interesting side-light on this matter is that Winefride is the patron saint of ‘women affected by unwanted advances’.

Artwork

Whatever the back story, the panel is still magnificent. The slash of red (the colour of martyrdom) cuts across the scene, and the overcast, purpling sky is a triumph of abrading. The flowing blue stream (which will play a part in the miracle to come) contrasts with the red.

Hours of work must have gone into this work – despite the fact that it is a relatively small scene in the overall design of the whole of the West Window.

For Marga, it must have been important.

+

If you’d like to comment on this article, please use the Comments Box below

You can read a description of all the scenes in the West Window by accessing Roger Hall’s monograph on the Ropes Website or by buying a copy of his booklet ‘Letting In the Light’, a new version of which is available from Shrewsbury Cathedral.